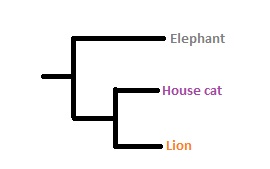

For example, if you wanted to build a key to tell you what each of the four objects below were called (if you had never seem them before) it might look something like this:

The object doesn't have eyes (go to 3.)

2. The object is yellow (Mustard the dinosaur)

The object is orange and purple (A spider)

3. The object is soft (a beanie)

The object is hard (bamboo plant in red holder)

Each of these steps is called a 'character' and in a dichotomous key, each character can have two states. In step one, the character is eyes. The first state is having eyes, whilst the second state is not having eyes.

We are following dichotomous keys like this for the wasps - trying to work out what they are (even though these ones have labels on them) so that when we start finding new wasps we are used to using the key and can identify them easily.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed