|

Just a quick update to say that Mustard and I are still reading journal articles and writing our literature review. We're starting to get a pretty good idea of what scientists have done in the past, and where our project could fit in. Not much new happening, although plans are under way for our lab-group retreat next week. All the researchers and students in our lab are going away together to have some time for meetings, insect collecting, and the chance to share what we're doing. Mustard is helping to make very important decisions like how much chocolate should be on the shopping list...

0 Comments

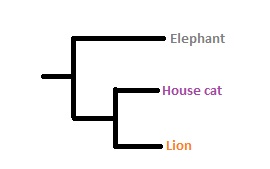

Mustard and I are of course still reading, note taking and starting to write our literature review. Technically this isn't due until six months into our Ph.D., but we really don't want it to take that long! Getting it done faster means more time for actually doing the science!  A simple phylogeny - house cats are more closely related to lions than either of them are to elephants. A simple phylogeny - house cats are more closely related to lions than either of them are to elephants. Today we are thinking about how we are going to sequence the genes of our wasps. Originally, a taxonomist (a person who finds and describes new species) would use the morphological characteristics (what it looks like) of an animal to work out how it is related to other animals, and whether it is a new species or not. For example, a lion looks pretty different to a house cat, so by looking at them we might guess they are different species. We would also probably be able to say that they are more closely related to each other than either of them is to an elephant. Scientists represent this as a phylogeny - like a tree of life. With insects it can be a bit trickier. For one, they can be really tiny! They also sometimes show a lot of convergence - this is when two insects have a body part that looks the same, not because they are closely related, but because they both needed that body part to do the same job. You've probably noticed this in birds, bats and bees - they all have wings, but they're not closely related! They just all evolved wings so that they could fly. So if we were to group animals just based on whether they had wings or not, we wouldn't get a correct idea of their relationship to each other. These days insect taxonomists often use the help of molecular data as well as morphological. Inside every living thing is genetic information (like DNA or RNA) and by comparing how similar the DNA of a group of insects is, we get an idea of how many species there are and how they are related to each other. There is so much DNA in an insect though, that at the moment it is impractical to use all of it. So scientists working with molecular data tend to use just a few genes (genes = particular lengths of DNA. Jeans = cool denim pants). Up until a few years ago, most people working on insects would use between three and six genes to build a phylogeny. A journal article (what's a journal article?) published last year used 1,478 genes to build a phylogeny of the insects. 1,478! That's a lot of genes!  Mustard is curious about what parasites dinosaurs used to live with. This is a magnified human head louse - I wonder if dinosaurs had lice on their skin too? Image of head louse by Gilles San Martin, CCBY-SA 2.0, as seen on the Wikipedia 'head louse' page. Mustard is curious about what parasites dinosaurs used to live with. This is a magnified human head louse - I wonder if dinosaurs had lice on their skin too? Image of head louse by Gilles San Martin, CCBY-SA 2.0, as seen on the Wikipedia 'head louse' page. Today Mustard and I are doing more reading, so I thought it was past time that I told you a little about the wasps that we are studying. We are looking at a group of wasps called the Microgastrinae. This is a subfamily within the Braconidae family of Hymenoptera (see our last post for an explanation on classification). The Microgastrinae are endoparasitoids of butterfly and moth caterpillars. A parasite is a living thing that must live on or in another living thing to survive. Some parasites you may have encountered before are animals like head lice, which live on human scalps and feed on blood. Mites, leeches and gut worms are other parasites you may have come across before. Parasites tend to keep their host (the living thing they are feeding from) alive. Our wasps are endoparasitoids. Parasitoids, unlike parasites, end up killing their host to complete their life cycle, and the adult parasitoid is normally free-living (doesn't need a host to survive). The 'endo' part of their name means they live inside their host. An ectoparasitoid lives outside the host (for example on the skin or hair of animals). A female microgastrine wasp will lay her eggs inside a caterpillar (sometimes just one egg, sometimes lots of eggs) and then leave them to develop. The eggs hatch and the baby wasps (called larvae) feed off the inside of the caterpillar as they grow. When they are fully grown larvae they chew their way through the skin of the caterpillar and crawl their way out! This kills the poor caterpillar, but the baby wasps have grown big enough to form a cocoon and change from a larvae to an adult wasp, starting the cycle all over again. It's disgusting and reminds me of something from a horror movie, but also incredibly fascinating! Watch this amazing footage of a caterpillar infected with wasp larvae. The dialogue is in Spanish, but you can see the larvae burst out of the caterpillar, form cocoons and then emerge as adult wasps! Mooooore reading. And note taking. Mustard and I are learning that scientists have to read A LOT about their research project before they start. Today we are learning about viruses! Viruses are microscopic (really really tiny!), super fascinating things that infect living cells and can cause huge changes in their host. There is still a debate amongst scientists whether viruses should be classified as 'alive' or not, because they can't reproduce outside of the living cell they have infected. They can, however, pass on their genetic information (like their DNA, or another type of genetic information called RNA) to future generations, and they evolve through natural selection. You probably had a virus inside of you last time you had a cold - there are several viruses that infect humans and give us all those annoying symptoms like a runny nose and a sore throat. Isn't your Ph.D. about wasps, not viruses? (I hear you ask)

We are reading about viruses because the wasps we are studying (see our last blog post for a cool video of the Microgastrine wasps infecting a caterpillar) have a type of virus inside them, called a polydnavirus, that seems to help the wasp lay her eggs inside caterpillars. The virus doesn't seem to hurt the wasp at all, but they are passed into the caterpillar when a wasp lays her eggs. The virus does harm the caterpillar, by weakening its immune system. The immune system is what destroys cells in your body that don't belong to you and protects you from disease. The polydnavirus therefore protects the wasp egg from being attacked by the caterpillar's immune system. The wasp and the virus appear to have what is called a mutualistic association. This means that they help each other, without harming each other. The wasp provides a nice comfy home for the virus to live and replicate in, and the virus helps the wasp's eggs survive inside a caterpillar. Another well known type of mutualistic association is between clownfish and anemone, like in Finding Nemo! The clownfish are protected from predators by the stinging tentacles of the anemone, and in return the clownfish clean the anemone, provide nutrients in the form of waste, and scare away the butterfly fish which like to eat anemone! Unsurprisingly, Mustard and I are still busy reading scientific journal articles and taking notes. We will probably do this for many weeks yet! Today we also joined a few societies that relate to our research. Being a part of societies or organisations is a great way for scientists to connect with other scientists in their field. Most scientific societies are a bit like joining a club - they might have meetings you can go to or a regular newsletter or magazine that you can read.

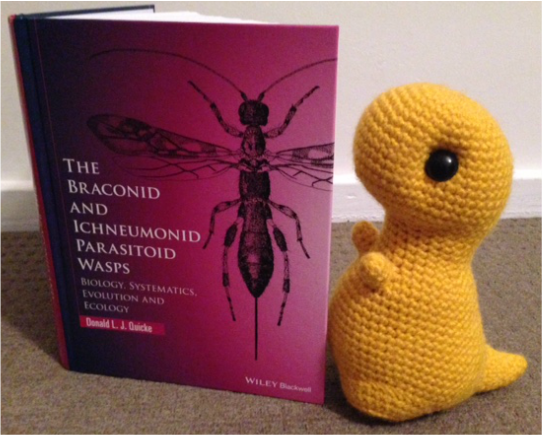

We joined the International Society of Hymenopterists. A Hymenopterist is a person who studies 'Hymenoptera' - the scientific name for bees, ants and wasps. All life is classified on the basis of how it is related to other living things. Wasps are classified in the order 'Hymenoptera' which is in the class 'Insecta' (the insects), which is in the phylum 'Arthropoda' (animals with their skeleton on the outside of their bodies, jointed legs and a segmented body), in the kingdom 'Animalia' (the animals!).  Mustard is using the Web of Science online database to find journal articles to read. Mustard is using the Web of Science online database to find journal articles to read. The first step in any research project in science is to find out what has already been done. Scientists tell other scientists about their discoveries by writing journal articles. A scientific journal article will explain what you wanted to do (your aims), what you actually did (your methods), what you found (your results), and then what you think this means (your discussion). Before starting a project or doing any experiments, it is important to read all the journal articles that relate to what you are studying. Otherwise you might accidentally spend a long time doing experiments that have already been done! It is also a great way of finding out where the gaps in our knowledge are, and what experiments or research would be most useful to fill those gaps. Before the internet was so widespread, scientists would have to go to the library and find hard copy journal articles to read. These days almost everything Mustard and I will need is online. The University has an online library, and there are databases where you can search for a topic (such as the name of the wasp we are studying) and it will find all the journal articles about the topic for you. The internet has made it much easier for scientists to read and keep up to date with what other scientists in their field are doing!  Today Mustard and I had our first meeting with our PhD supervisor and borrowed some reading materials (one really big book!) to help us start learning about the wasps we will be studying. PhD stands for Doctor of Philosophy. It's a research project where you study something that gets you really excited, for about three years! It is normally the first time a scientist gets to choose what they are researching and what experiments they are going to do. PhDs are not just for scientists. People do PhDs in all kinds of things! For example you can do a PhD in nursing, music, history or art! A supervisor is a person who has lots of experience in what you are studying. They are there to help and guide you through your experiments, and offer advice when you get a bit confused or unsure of what to do next. |

AuthorPhD student and her trusty dinosaur explore the world of science. Check out our Citizen Science Project, The Caterpillar Conundrum! Archives

July 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed